Place

Hors-série / Special issue 7

Juin / June 2020

ARCHIVES

LA UNE / COVER

Good to meet you at last, Joachim began. It’s been ages since we’ve seen Catherine, maybe three years?

He looked in Irmgard’s direction, but his gaze missed her completely and rested, momentarily, but with visible disapproval, on a bright red pen in the server’s apron. Irmgard nodded as if she had actually been asked whether it had been three years, and smiled at me as if to say, This is how it is.

I ordered sparkling water, and soon the evening was underway: a monologue from Joachim, covering his acquaintance with Catherine, beginning with their years in England; the scene there; his move back to Switzerland; the execrable weather, worse than England if that was even possible; the little house they had bought in a forest near the Tegel airport in Berlin, how lovely it was in the springtime and yet how remarkably infested with spiders; their dog Teddi who bit a neighbor’s girl, thinking she was attacking their own daughter Ingeborg; Ingeborg’s childhood allergies; Ingeborg’s freckles; Ingeborg’s pimples; Ingeborg’s broken second toe on her right foot, which she stubbed on a half-buried plank that turned out to be an entire collapsed shed their neighbor had let decay, creating a minefield of rusted nails and splinters; the pusillanimous left-wing coalition that threatened to undermine Switzerland’s exemplary position in regard to the EU; both World Wars; the dependably low quality of German and Austrian students, in relation to the possibly higher quality of Canadian students and the definitively far superior level of the few American students he had had the privilege of teaching over his twenty-four years of uninterrupted service to the University of Basel, which, despite all its inconceivably stupid fiscal decisions and its nerve-wrackingly incompetent administration, all of which amounted to a more or less devastating emotional and intellectual experience for the faculty, had nevertheless managed, once again, to secure a Swiss National Science Foundation grant as a Center of Excellence in the Biological Sciences, which led him, and this, of course, or so he assumed, would be no surprise to me, to be able, indeed pleased, to invite me to come to visit for at least a semester and perhaps as long as a year.2

_______________________________________________

Note 2

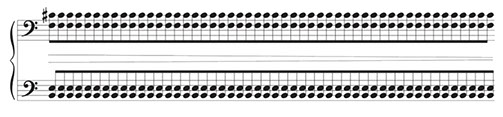

In 1953, Karlheinz Stockhausen had the idea of composing a piece for piano that would begin by repeating one chord, hammering on just one chord, over and over, until it started to sound a little different each time, even though it would actually be the same chord, over and over, with no variation at all.

It would not be an ordinary chord, but a strange one, dissonant, not really in any key, a puzzling chord, and it would just be repeated over and over, starting as loudly as the pianist could possibly play without breaking keys or fingers.

When I am ready to play Piano Piece 9, I position my hands a half-inch above the four notes of the chord, B, E, F, C♯. I hit the keys as hard as I can, punching down with my fingertips. The first measure is exactly one hundred and sixteen beats long.

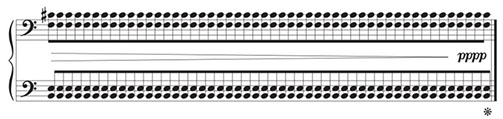

I count as I go. The notes move fast, so I count in twos. The loudest chords hurt my fingers, but I have to play accurately, because the chords get quieter, in one hundred and fourteen imperceptible and equal steps, from deafening to nearly silent.

The last couple of repetitions are marked pppp. They should be just barely audible in a quiet room. When I reach the one hundred and fourteenth chord I hold it briefly, for just two more beats. It’s as if there are two more chords, so quiet they are imaginary.

Then it begins again, eighty-three more repetitions of the same chord.

Again I play as loudly as I can. Again I gradually diminish the sound, as smoothly as I’m able, until my fingers are just barely grazing the keys, so the notes aren’t even a whisper.

I suppose that for a person hearing this for the first time, that second set of chords must be a special kind of torture, because if the composer can do it twice, he can do it twenty times, and if he can make up numbers like 116 and 83, then what’s to stop him writing a measure 1,000 beats long, or 25,000? A first-time listener will think the piece is going to be nothing but the same single excruciating chord, hammered over and over, diminishing to nothing, then starting again.